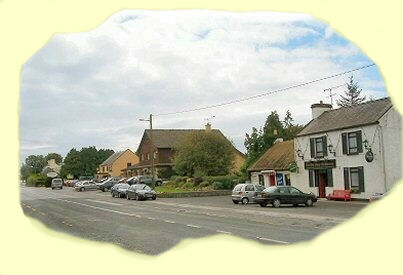

Village of The Neale

|

Entering the village of The Neale from the north on a late summer evening |

|

|

On my visits to Ireland, I have always been drawn to the district of The Neale where, according to my father, my ancestors had lived in Turloughmore for many generations before moving to Cahermaculick in 1917. Apart from the role it played in their lives, this pleasantly quiet and very attractive part of Ireland is steeped in history. It was to the plains of Moytura just outside the village of The Neale that the noted Irish scholar Seumas MacManus went early last century for the subject to the opening chapter of his magnificent book "The History of the Irish Race". It was there in the year 3303 BC that the ownership and control of Ireland, for at least a few thousand years until the arrival of the Celts, was determined in the battle that took place between the Firbolg and the Tuatha De Dannan.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Across its landscape are many monuments that speak of the different ages of Irish history from the most ancient times to the present. Cairns and stone circles from the Neolithic and Bronze Age Periods, raths or ring-forts from the Early Iron Age (sixth century BC in Ireland's case), crannógs from Neolithic times right up to the Middle ages, monastic sites from the early Christian Period as well as stone abbeys from the early Medieval Period, many castles from Norman times with the De Burgo family responsible for most of them, as well as a host of other fascinating and sometimes unusual monuments. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Close to the ruins of Lord Kilmaine's house is a fascinating stone monument. Central to it is a stone slab with carvings of a human, an animal and a reptile which are referred to as the Deithe feile (The Gods of Welcome),Dia na Ffeale or 'The Gods of The Neale', 'The Neale' being the anglicised form of 'na Ffeale'( of welcome). The slab itself was found in a cave in 1739 close to where it is now enshrined. The Lia Lugha (Stone of Lu) that stands at the fork of the roads to Cross and Cong just south of the village of The Neale is said to mark the burial place of Lugh Lamhfhada (Lu of the Long hand) who was slain in the Battle of Moytura. He was the son of Nuadha, king of the Tuatha De Danann. |

||

|

|

|

Just north of The Neale on the Balinrobe side is the first of two unusual stone structures, a step pyramid approximately 9 metres(30 ft) high and 12 metres(40ft) wide which was built about1760. According to the Browne family, it was built by John Browne, the 1st Baron of Kilmaine, in memory of his brother, Sir George Brown. One of the more plausible stories, according to locals, explaining the reason for its building is that lord Kilmaine in his efforts to alleviate the extreme poverty of his tenants employed them to pick up the stones around his estate and had them built into a pyramid. I am quite convinced that this story demonstrates only one thing which is the capacity of the local people in their comfort today to be a lot more generous in thought and spirit towards those who usurped the lands of their ancestors, forcing them to live in extreme poverty and stripping them of all their rights including their age-old Celtic name and dignity. |

|

|

The second of those two unusual stone structures is a Doric-like temple. It was built by John Brown, Baron of Kilmaine, in honour of his first title of Lord Mount Temple. It was made of carved stone, but never quite finished. The base was built sometime before 1865 when the Doric columns were added to give the structure elevation. It was used by the ladies of the Big House for family meetings and relaxing. It was during the 18th century that the great houses and estates of the landlords were built and enclosed by high stone walls. It was during this time also that the Irish people were subjected to unparalleled deprivation and suffering with the introduction and enforcement of the Penal Laws. The Neale estate of lord Kilmaine was about 400 acres, but in Co. Mayo alone he owned 114,000 acres by 1710. |

|

|

|

|

|

John Browne*, the first English man to settle in The Neale in the 1580, was an accomplished sailor and explorer. He was granted land there by Elizabeth 1 for services rendered to the crown. The initial grant was thirty quarters where each quarter was 125 acres, a very handsome grant by any standard of others' land to a loyal subject! This was the impetus for the Browne family's acquisition of thousands of acres of land throughout Mayo and elsewhere in Ireland. It was conveniently sustained on a grand scale by the events which followed the fall of Ulster and the signing of the Treaty of Mellifont by Hugh O'Neill himself in 1603. Ulster had proved a most difficult province to subdue, and the Flight of the Earls in 1607 stirred ever so darkly the hearts of the Irish. The Tudor conquest was now complete and the old Gaelic society was doomed. The three hundred years of persecution that followed has no parallel in the annals of human history. England's energies were so ruthlessly concentrated, as if no one should care, upon the utter and most heinous annihilation of the Irish race. The Cromwellian** and Williamite** wars, as well as the Penal Laws**, were to recover Ireland at all costs for England and to exterminate the Catholics. They are unsurpassed in history for their brutality, butchery and betrayal where the lack of honour was absolute, and they make Machiavelli's strategies in The Prince for gaining and keeping control pale into insignificance. Cromwell's massacres at Drogheda and Wexford, condoned and applauded by the English Church and Parliament, read like pages of Nazi atrocities in Poland and the Ukraine. |

|

| *He became sheriff of Mayo in 1583. It was John Browne, head of the seventh generation of the Browne Family who first received the title of Lord Kilmaine. Thirteen generations of the Browne family lived as landlords on The Neale estate until 1925 when they moved back to England. Holding on to the title, the present Lord Kilmaine resides in Alcester in England. | |

| **Click here for more information | |

|

The conquest of Ireland appeared completed. The clan and communal system was overthrown and the great Gaelic Houses destroyed, and centralisation established by a despotic power. This placed the government, power, patronage and the ownership of the land in the hands of the colonists. Yet, the conquest was as Seumas MacManus describes it only "surface deep. On that surface the English Law ran, and her armed forces moved. But the soul of the Irish was unconquered." The uprisings continued only to be crushed time and time again. The English recognised that the bulwark of Irish nationality was the Irish language and made every effort to destroy it. The memory of Brehan Law still survived as was demonstrated in the Land League founded by Michael Davitt at Castlebar in 1879 and in the on-going agitation by the Irish people for ownership of the soil. During the 1870's the plight of the Irish tenantry was desperate. It is so difficult for us today to really understand the condition of affairs in those bygone years. It is made even more difficult by our tendency to want to feel comfortable with our humanity. The landlord was "the master". He could raise rents at will, and could evict whether rent was paid or not. If the tenant improved his holding, he could be taxed for doing so - the rent went up. If he defended the chastity of his daughters, or they did so, he was liable to eviction. The landlord owned the tenant, and the tenant's land, and the tenant's vote, and, as he thought, sometimes even his tenant's women-folk. Rack-renting and evictions were rife. The evicted tenant who made his home on a strip of waste bog was rented, when with the sweat of his brow he had converted it into land so called. |

|

|

Mayo was one of the worst counties for rack-renting and evictions. It seems proper then that the first organised assault on landlordism should be made there. The imminent danger of famine supplied Michael Davitt and his Land League movement with additional momentum. The crop of 1879 failed. Rack-renting worsened. The landlords demanded payment for the land which the land never earned. England's Parliament refused to do anything to remedy matters. Between 1870 and 1876 fourteen attempts to amend the Land Act failed. Every motion in that direction was rejected with scorn. Little wonder then that the Irish people took matters into their own hands. What were calls for a 'fair rent' were quickly changed to ones of 'no rent'. Meeting after meeting was attended by tens of thousands. Michael Davitt and James Redpath, an American journalist who had already risked life and fortune in the cause of human freedom, outlined to farmers the system that was soon to be known as 'boycotting'. Mayo was ablaze and an extraordinary revolution had begun. Charles Parnell who had recently been elected to the House of Commons threw his weight behind the movement, exhorting the farmers on the 19th of September 1879 to adopt the policy that "When a man takes a farm from which another has been evicted you must shun him on the roadside when you meet him, you must shun him in the street of the town, you must shun him in the shop, you must shun him in the fairgreen, and in the market place and even in the place of worship. By leaving him severely alone, by putting him into a moral convent, by isolating him from the rest of his countrymen as if he were a leper of old, you must show him the detestation of the crime he has committed." This at last was the powerful weapon to be used against rack-renting and evicting landlords, bailiffs, land grabbers, process-servers, rent-warners and all the crowbar brigade. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Neale area played a prominent role in this struggle. Almost half of what were termed 'agrarian outrages' of the late 1870's and early 1880's, such as the maiming of cattle, destruction of property, wounding and even killing of land agents and landlords and those who were considered 'land grabbers', occurred in Mayo, west Galway and Kerry. In that same month of September 1879, the district of The Neale attracted international attention, and in the process gave a new word to the English language, by initiating a rather novel form of non-violent protest. This involved a campaign of ostracisation against Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott (agent for Lord Erne), who lived at Lough Mask House close to The Neale. It all began when, on instructions from Lord Erne an absentee Lordlord, he offered only a 10% reduction in rent and not the 25% demanded by the tenants. He also dismissed his labourers owing to a dispute over wages. No others would take their places. The Captain was so furious that he decided to have eviction notices served against 11 of his tenants. On the 22nd of September, David Sears accompanied by 17 constables set off from Ballinrobe to serve the notices. The women of the Lough Mask area descended on them with stones, mud and manure, forcing them to take shelter in Lough Mask House. When they tried again next day, a swell of people rushed from Ballinrobe to support the women of Lough Mask. The action had been inspired by the parish priest of The Neale, John O'Malley and James Redpath. The people swamped the estate, invaded the house and advised the servants to abandon their posts. The first 'Boycott' has begun in earnest. The blacksmith was too busy to shoe the Captain's horses. The herds found the weather unhealthy. The baker ran out of flour. The 12 year old postman was liable to overlook Lough Mask House, unless his missives for the Captain were unmistakably bills. The Captain's crops were ripening with no one to harvest them. But relief was coming in what was described as the 'Boycott Relief Expedition' and the 'Boycott Relief fund' established by the Belfast Newsletter. |

|

|

Fifty northern Orangemen escorted by two thousand soldiers arrived in Mayo to assist Captain Boycott. A campaign against the 'Boycott Relief Expedition' was effectively orchestrated by Father John O'Malley. It was he who suggested to James Redpath, special correspondent of The New York Herald, the term 'boycotting'as being easier for his parishioners to pronounce than 'ostracisation'. When the expedition arrived in Claremorris, there was not a vehicle or horse in Claremorris fit for the job of transporting any of them. The labourers and their escort had to walk the fifteen miles from Claremorris. On arrival, they encamped on the Captain's lawns. No provisions for their stay had been made. As they were doing the Captain's work, they presumed that they were to be fed at his expense. They ate his turkeys, geese, piglings, goslings, ducklings and all other of the most succulent part of his possessions. Apart from what it cost the Captain, it was estimated to have cost the country over ten thousand pounds, ten pounds for every pound's worth of crop harvested on his land, or as Parnell said, "a shilling for every turnip dug". |

|

|

By late November, Boycott realised that all his efforts had been in vain. On the 26th the northern expedition left Lough Mask staying over night in Ballinrobe. The following day they set off on their journey back north, and were passed on the road by Captain Boycott, his wife and his niece in an ambulance wagon which they had to borrow. They returned to England until the agitation had subsided. |

|

|

|

|

|

Needless to say, the "outrages" were not all on one side. Gladstone's Chief Secretary, known as Buckshot Foster, had replaced his Royal Irish Constabulary's rifles with shotguns which he described as more treacherous when discharged on a crowd. He proceeded in the traditional way to pacify Ireland by arresting all the leaders and organisers. His Buckshot Brigade loyally and zealously carried out their master's orders. In addition to the buckshot, the peelers were provided with a more deadly type of bayonet. A few examples will suffice to show how the orders to break the spirit of the people were carried out. At Grawhill, near Belmullet in October 1881, a crowd assembled, chiefly composed of women and children. The officer in charge of the crown forces gave orders to fire a volley of buckshot into the crowd and then charge with the bayonet. Numbers were wounded; the crowd rushed away in shrieking panic, the police freely using their bayonets indiscriminately on all they came up with. Mrs. Mary Deane, a widowed mother, was shot dead; a young girl, Ellen McDonagh, was stabbed to death. On May 5th, 1882, a band of lads of twelve years and under paraded in Ballina, County Mayo, with tin whistles and cans to celebrate Parnell's release from prison. They were assailed with a hail of buckshot, chased and stabbed. One poor lad, Patrick Melody, fell dead at his father's feet on the threshold of his home. |

|

|

Great numbers of Irish emigrated, many dying on their way to a foreign shore. It's perhaps just as well that the dead do not talk! The years immediately after the great famine and right up to 1900 took such a heavy toll of lives. The Irish were down but not out and so put the boot in more forcefully still! So many speakers like John Mitchell and writers of the eviction horrors give terse and terrible summaries and descriptions of the happenings upon estate after estate throughout Ireland. |

|

|

The Land League went ahead. The leaders were arrested and imprisoned but Davitt had laid his lines well. He had established the "Ladies' Land League" where he relied, and he wasn't disappointed, on the women of Ireland to carry on, even if all the leaders were in prison. Huts were erected for evicted tenants and relief works were started. The landlords' power was beginning to slip and their grip on the land was slowly weakening. Yet the coercion, oppression and poverty which had caused for centuries so much misery and pain were to continue for another forty years. By 1903 when my father was born, life was improving, albeit ever so slowly, for the people of Mayo and elsewhere. Some measures were adopted to cope with the failure of the potato crop. The development of the Irish railway was organised and a bill for land purchase was introduced under which the tenants became full owners of the land. A board was constituted under the new Congested Districts Act but its powers to transfer tenants from the many congested areas were so limited that it realised only minimal success. Some sixty years later, when I was about to leave Ireland to settle in Australia, the government was still relocating families from our area to the rich plains of the midlands. |

|

|

|

|

|

Boycott returned to Lough Mask after an absence of one year without undue fuss or hostility towards him. But in 1886, he returned to England to sell his lease at Lough mask, having the added bonus of 2000 pounds which he received from public subscription. After the turn of the century, my father and his parents and family who were tenants of Lord Kilmaine in Turloughmore moved from there to Cahermaculick where they purchased land under the state-aided land purchase scheme. Whatever the merits of the scheme, it was very seriously flawed in its design to more than handsomely 'compensate' the landlords for the land handed over to the scheme. My grandfather and my father and the other farmers like them were saddled with a gnawing debt for over sixty years which in one of the most twisted ironies of history the landlords and English government described as 'just' reparation! On the initiative of a Galway landlord, Capt Shawe-Taylor, representatives of landlords and tenants met in 1902 to discuss the land problem. They reached an agreement on the basis of long term purchase which would secure the landlords against any loss by making the cost of purchase of their farms considerably higher than it should be while at the same time enabling tenants to secure money at a low rate of interest, and thereby secure them their land at a fixed annuity which would be lower than the actual rent. |

|

|

This agreement resulted in the Land Act of 1903 which was welcomed by the tenants as a means of getting rid of the landlords at all costs. The tenants' champion, Michael Davitt, passed away in 1906. Charles Stewart Parnell had also passed from the scene having died on September 27th, 1891, leaving a vacancy that none of his fellow parliamentarians were able or willing to fill. The English leader, Gladstone, the one statesman who could be compared with him, regarded Parnell as an "intellectual phenomenon". Sadly the years from 1892 onwards for some thirty years were characterised by strife, bitterness, aggression and further coercion and oppression. The performance of the Irish Parliamentary Party was nothing short of disgraceful, and its involvement in the question of self-government for Ireland compromised Ireland's every claim to nationhood. In 1906, when the British Liberals were returned to power, Birrell, the newly appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland, introduced the Irish Councils' Bill, a sort of enlargement of the Local Government Act of 1898. Irish Parliamentarian John Redmond was in favour of it until he learned the temper of Ireland. |

|

|

The Irish Parliamentary Party had become dictatorial in its management of Irish affairs. In 1914, a play-at 'Home Rule' Act was passed allowing the Irish to play at a "Parliament" in Dublin. Its enactments could be vetoed by the British Parliament or the British Lord Lieutenant or ruled illegal by the High Court of Justice, and Ireland's finances were to remain in England's hands. This was the nation's "great charter of liberty" according to the Irish Parliamentary Party and it begged and begged Ireland to accept it. Parliamentarian John Dillon in the House of Commons solemnly pledged, for Ireland and his Party, that the Act would be accepted as a full and final settlement of Ireland's claims! The Party had now become the pawn of the British Liberals. But when the Home Rule Bill became law, it was immediately postponed, not because of the war as some people seem to think, but because Edward Carson forbade its implementation. |

|

| *Click HERE for an account of the Black and Tans | |

|

It seems fitting to conclude this page on The Neale with a picture of the latest monument to be erected there. It is known as the Fr O'Malley Fairgreen in honour of John O' Malley for not only his role in the success of the Land League movement but also for his tremendous support of his parishioners during the dark days of near famine and crop failure during the 1870's and 80's. He laid the foundation for future generations by building the old Neale school in 1883 and the existing church in 1875. This monument was erected from the stone from the old school and church. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|