Back to Australian Branches ‹--------› Forward to Martin's Family Tree

As years went by, I had quickly lost contact with my classmates after leaving Carrignavar in June 1954. The very poor state of things in Ireland meant that I followed in the footsteps of millions of Irish before me. Time and circumstances over such a long period had seen to it that it was very much part of the Irish psyche to accept and indeed expect the country’s youth to emigrate. So for me and those tens of thousands like me, the pier beckoned as it were and inevitably its call was answered. I was not to meet any of my classmates again until 1969 when Tom Kilgallon was visiting Sydney on business from New York. Tom had obtained a masters in both chemical engineering and administration from Columbia University New York and was employed by one of the oil companies. We have met twice since 69. When my two sons, Martin and Michael, and I were returning from a visit to Ireland in 1974, we stayed with Tom and his family in Matawan New Jersey. Twelve years later in 1986, Patricia, Kieran and I met by chance Tom and his family during our visit to Ireland. We travelled the Ring of Kerry together and visited both Western Road and Carrignavar. The years passed and I didn’t hear from Tom again until November 2006 when I received an email where he had come across the family website. Tom has retired and Mary and he live in Naperville Illinois not far from their children and grandchildren.

|

This picture of some of my classmate means a lot to me as a reminder of the wonderful years we spent together in Cork. We had I think twenty one in our class and to a man they were all fine students and sportsmen.

Standing L to R: |

|

|

I received a letter from Colm O’Grady just before Christmas 1954. He was my best friend throughout College. I left Ireland shortly after receiving his letter and I never did get round to answering it. In 1958 when I visited my family in Ireland before leaving for Australia, I had intended calling on him at the Order’s Moyne Park College in Co. Galway but learnt that he was studying at the Irish College in Rome. As I learnt when I visited Carrignavar in 1974, Fr Colm O'Grady was killed in a plane crash outside Istanbul in January 1971 when he was returning to Louvain University after visiting friends he had made in Istanbul during a lecturing tour there. The moment I heard this I remembered seeing it on the news and reading about it in the newspapers and had wondered back then why this particular accident had grabbed my attention. He completed his studies in Rome with Doctorates in Philosophy, Divinity and Christology. He was a prolific writer and by the time of his untimely death aged thirty four, he had scholarly books on Christology on the shelves of all leading universities and other educational institutions across Europe and elsewhere. In fact he had already established himself as Europe’s foremost authority on Christology. Tom Kilgallon met him a number of times during his national service tour of duty in Europe. He had this to say in a recent email: “As you know, Fr Colm O'Grady was killed in a plane crash near Istanbul when he was teaching at Louvain University in Belgium. Many of the Americans in Brussels knew him well because he said Mass often at the American Church outside Brussels where we attended.”

My brother Mick who had come home for Christmas 1954 didn’t look any the worse for having worked most of the year in Birmingham, and so when he was returning on the 4 January I joined him for the trip across the Irish Sea.. I was seventeen at the time and it was a bitterly cold and miserable Birmingham that greeted me. I don’t think I had ever seen so much snow and ice in the one place at the same time. I had experienced as a youth heavy snow falls in Mayo and Cork but nothing like this. Fortunately, I was able to stay at the same boarding house as Mick, but I never got to like it there. Early next morning and knee high in snow, we made our way to the nearest tram stop guided through the dark and smog by a few pale gas lamps. Mick was returning to work at Cadbury’s and knew that they were looking for employees. With about five others, I was led into this big room and handed a heap of forms to read and complete by this mustachioed and military like official who obviously took pride in having won the war for England and was now enjoying his just reward. What followed was the first of a number of interviews that took up the whole day. When it was time to leave, Mick was nowhere to be seen. That would have been fine if I had known where we were staying and the tram to catch there. I looked in every direction but nothing clicked. After all it was still dark when we had arrived there in the morning. In desperation, I jumped on a tram, any tram, not knowing where it was going or what to look out for. I kept my eyes fixed on the footpath and fences looking for anything that might be of help. Suddenly this leaning spluttering gas lamp came into view and I jumped to exit the tram. It was the house. I was there.

|

I enjoyed working at Cadbury’s. Most members of the team I joined were from Germany and were quite intelligent having completed second level and some third level education. I was the youngest member of the team, fresh out of college and a Catholic one at that. I didn’t realise I had so many beliefs to defend or justify, and so coming to work each day was like having to tackle a new treatise. Traditions, customs, attitude towards life and religion all featured in our discussions and debates. At first it was rather daunting but I did get to like it and certainly missed it when I left there four months later to join the City Corporation in order to become a bus driver. By then Mick and I had moved to lodgings in Grantham Road, Stoney Lane. A couple of months later, Mick sailed for Australia. Of course I was too young to apply for a public transport licence and so had to assume our oldest brother’s identity. It was strange at first responding to his name. I enjoyed my eighteen months on the buses, driving and travelling to new places and meeting so many different people. When I moved to London at the beginning of 57, I reverted to my own name to avoid national service. I worked for the British Railways Department in it office at Cricklewood. During my free time I studied Mechanical Engineering in 1957 and 1958 at the Baker Street Polytechnic. |

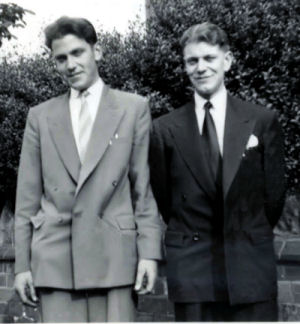

Mick & Martin Coleman Grantham Rd Birmingham 1955 |

When national service began to raise its head again, I decided to head for Australia. In early May, I attended an appointment at Australia House, completed all the forms, underwent a medical and received the necessary vaccination. In a meeting that followed later that afternoon, I was given my identification document and told to be ready to sail in June at fairly short notice. As it so happened, the telegram arrived on 17 June, the day before my 21st Birthday. After fixing things up at work next morning, I headed home as I wanted to see my family before sailing. It was lovely to see my family again and while Dad and Mam were very sad to hear of my plans, they found some comfort in the knowledge that I would be joining Mick in Sydney. The weather was beautiful as I drove around with Dad to visit my relatives and I wished I had a couple of weeks rather than just six days. I remember our visit to my Grandparents in Glencorrib as if it were yesterday. Mam didn’t want to come with us. It was obviously too much for her. I can clearly recall how, when we were all seated at the table to one of the biggest bacon and cabbage meals I had ever seen, Grandad stood up and stayed standing there ever so quietly despite being told by Grandma to sit down and have his dinner. I could see that Dad was trying to act as if nothing was happening. Then I felt the gentle grab of my hair to the words, “Sure I’ll never see ye and Sonneen (Mick) again it’s so far ye’re goin’”. Back home, my memory of the scene in the kitchen as I left Mam and my sisters could be no more sharply etched. Mam was in a terrible state. The tyranny of distance back then must have been so real and troubling to our parents. I often think about this and how unfair it was to have to put our parents through such an ordeal. Noel and Dad took me to Galway to catch the train for Dublin. I had the worst headache I have ever experienced and as I boarded the train Dad asked two students returning home to England from University College Galway to look after me as I wasn’t well. As the train pulled away, Dad kept running along the platform waving goodbye hat in hand. This and our parting in Cork eight years earlier are for me very special memories of my father.

Packing completed, I spent some time with John Joe and Bridie before setting out from 43 Lady Margaret Road Kentish Town on the morning of 26 June 1958 for Tilbury Dock on the Thames. About noon, I was a passenger aboard the ‘SS Orion’ as she pulled away from the quay on her voyage to Sydney. She was the biggest ship I had ever seen and I thought she was beautiful. I liked everything about her. She was considered to be one of the most famous ships on the Australian immigrant run as the first British liner with air conditioning in all her public rooms. After meeting a number of passengers on the first afternoon aboard, I couldn’t get over my luck in scoring such a comfortable cabin on C Deck which I shared with a young industrial chemist from Leeds. It came with two bunks alongside a couple of windows and had its own bathroom as well as washing and ironing facilities. I quickly realised, however, that my cabin mate’s expectations of Australia were quite different from my own. They were obviously derived from select readings about Englishmen who had transcended their status as only an Englishman can do with all the trappings that this type of success suggests. Yes, he was going to be surrounded by servants and maids and butlers in the colony, and in no time at all would feature in the same literature that ironically was the source of his delusions. Despite the fact that, like most others aboard, he was travelling under the Assisted Migrant Scheme, or the ‘10 Pound Scheme’ as it was more popularly known, he remained unfazed. He was no adherent of egalitarian principles and if by chance he had heard of the egalitarian Australian, he must have thought it was one of those myths associated with little known places.

From the outset, everything about the trip was interesting. Can you imagine my surprise to be seated at the same table in Dining Room A as the famous Dr Adams of Harley Street and Old Bailey fame! His trial took over three months and made for great reading in the daily papers. His wife and he as well as a fellow doctor, his wife and daughter were travelling to Greece on vacation. We met daily for breakfast, lunch and dinner and his wife, when she felt like joining us, seemed the most finicky person imaginable. She was always late to table and always asked to inspect just about every dish on the menu before, if at all, accepting one. I began to feel sorry for her as she looked both frail and sickly and the sight of food was obviously enough to make her unwell. Adams himself

|

Specifications: Tonnage: 23,371 GRT Length: 665ft (202.7m) Beam: 82ft (25.6m) Engines: Six Parsons SRG Steam Turbines Service Passenger Decks: 7 Crew:565 Passengers:708 Cabin Class,700 Tourist Class. |

was Irish from Dublin but had practiced all his life in London. I sat next to him at the table just across from his wife and the other ladies. I think there were eight of us at the table. Adams was quietly sociable with the knack of being able to involve everyone at the table in the chats and discussions that made for more enjoyable dining. We all dressed up for dinner usually in lounge suits but it was a black tie affair for Dr Adams. When I turned up one evening in suit and black bow tie, he was tickled pink to learn that I had just come from the Captain’s cocktail. Shortly after leaving Tilbury, the Pursar announced over the public address system that he was looking for volunteers to help out with the children aboard in areas such as reading, writing, arithmetic and swimming. I volunteered to take two small groups daily for arithmetic between 9.30 and 11am. The room was very comfortable and we had lots of fun. The ship certainly looked after its volunteers by providing them with special vouchers for free drinks and cigarettes as well as invitations to the Captain’s cocktail which commenced about forty five minutes before dinner. The black bow ties were provided by the Pursar. The affable Dr Adams seemed to take great pride in our turning up in bow ties the following evening and towards the end of dinner invited us to join him in the main lounge for drinks a little later that evening. In no time at all, one of the best parties aboard was in full swing.

Our ports of call were Gibraltar, Naples, the Port of Pylos, Port Said, and after sailing through the Suez Canal, Aden, Colombo, Fremantle, Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney. After crossing a relatively calm Bay of Biscay and enjoying some good views along the coastline of Spain and Portugal, we went ashore at Gibraltar. I was with eight other males ranging in age from twenty one to thirty four. A few of the older ones who had worked as lumberjacks in Canada showed remarkable experience in the ways of the world and certainly knew how to enjoy themselves. Whenever we went ashore, they seemed to know the best places to visit. It was the middle of summer and a warm one at that. I often think about our trip across the Mediterranean Sea. It was more a leisurely cruise across the most beautiful waters I had ever seen. The asure sky with its fluffy still clouds was a fitting companion to the very calm and sparkling blue waters. I recall how it reminded me at the time of the barrels of beautiful blue stone water prepared by my father to be sprayed on the drills of new potatoes. It was something that fascinated me as a child, those barrels of sparkling blue water located on the headlands from which stretched out in ever increasing numbers the uniform drills of all those tall potato stalks with their white and blue flowers as if nature somehow had outdone itself as surely it must have on this ocassion. I loved it then and I loved it more and more as we sailed further into the Mediterranean. It was a special experience like so many others that made this voyage for me the trip and holiday of a lifetime.

We geared up or so we thought for our trip ashore at Naples. After a boat trip to the Isle of Capri, it was down town to Mamma’s restaurant for the best food, wine and entertainment in this hectic city. Only two of us made it back to the ship before the gangways were raised and it set sail for Navarino Bay in the Messinia region of the Peloponnese in Greece. Left behind were my Cabin mate and about seven others and we heard nothing about them thereafter. Though we didn’t go ashore when we were in Navarino Bay, the views of Pylos as it rose up the hill from the harbour were magnificent. I had seen nothing like this before and it seemed so foreign and different. The scorched earth, the square flat-roofed buildings, the colours, all seemed so foreign and recalled the pictures in our school bible stories that my mother read to us as children. I would love to have gone ashore. As Dr Adams’ party and some others were preparing to disembark, there were a few barges of migrants approaching to come aboard. Dr Adams didn’t leave without going out of his way to say good bye and wish us well in Australia.

Our next port of call was Port Said before entering the Suez Canal as a member of a convoy without, of course, the escort of warships. The Canal had only recently reopened to shipping after the English-Egyptian conflict. As progress was slow, we had plenty of time to observe what was happening around the place. Dozens of Egyptian children were performing all sorts of aquatic stunts close to the moving ship and then diving to collect the coins thrown into the water by the passengers. All along the east bank, thousands of workers, ant-like in the distance, were excavating hills of sand bag by bag. The ship’s crew was busy covering

|

the main decks with tarpaulin in preparation for the ship’s stop in the Gulf of Suez in order to allow a convoy coming north to pass. This was the middle of summer and I had not ever experienced such hot and humid weather. I remember writing to my parents while the ship lay at anchor. When I finished the letter in one of the air-conditioned lounges, I took it to the Pursor’s office to be posted. Before I had time to place it in the envelope, it got so wet from my perspiration that I had to return to the lounge to rewrite it but not before I collected a towel from my cabin. This hot and humid weather continued until we entered the Gulf of Aden some days later.

When the ship docked at Aden, I was somewhat apprehensive at first about leaving the shops adjacent to the pier to travel, as the group suggested, by minibus to the centre of Aden, particularly after our freightening experience on the outskirts of Cairo after going ashore at Port Said. There were about twenty of us on the bus heading for El Giza and the Great Pyramid of Cheops and the Sphinx. When the bus stopped for petrol, we were surrounded by a mob that grew by the second. We didn’t know what to expect until the chanting started and by then it was too late to tell them that we weren’t English, not all of us at least, as the rocks showered down upon us. A few of us grabbed the driver and in pushing him behind the wheel, persuaded him to make a hasty exit out of mob’s reach.

Fortunately, it was a bus without glass windows and we counted our luck as we arrived back at the ship all in one piece. We should have known that many Egyptians were still hurting from the English bomb attacks during the conflict. It was about a twenty five minute drive to the centre of Aden. Along the way, we saw a number of chain gangs in their motley prison attire repairing the road. Aden itself was a disaster, a waste of time, and to say it was a shanty town would be to invest it with more respectability than it deserved. I don’t think that I have seen so many professional beggers in the same place at the one time. While we were still in possession of our dress, we headed back to the ship but not before encountering lots of beggers among the shops at the port. Loose change was all it took to satisfy them. Despite this, one of our kind resorted to pushing a couple of the younger ones quite forcefully out of his way and knocking them over. Obviously some code was breached but I didn’t stay around to find out what it was and must have gone under two minutes for the half mile back to the gangway.

If variety was what we wanted, the Indian Ocean didn’t let us down. This was sailing at its best and so far we had seen nothing like it. We encountered all types of weather from the very warm and calm to the cold and stormy. It was quite an experience to visit the highest bow deck during a storm and watch the mountainous waves pick the ship up bow first and then drop it bow first again into a big trough before repeating the action over again and again. Earlier on in the voyage, I had met a Scottish family of four from Greenock. They were on their way to South Australia. Their daughter, Catherine, had her Masters from Edinburgh University and was looking forward to taking up a teaching position. When we docked at Colombo, she and I went ashore together. She was interested in visiting the main store there owned by the parents of a student who was in her class at Edinburgh. A couple of hours later but not before we had enjoyed a lavish lunch, we were being driven to centres of interest on the Island in the store owner’s white Rolls.

King Neptune warmly greeted our arrival at the Equator in the customary manner. The ship’s horn accompanied by a rousing fanfare on the upper deck aft announced the occasion. The atmosphere engendered and sustained throughout the remainder of the day was second to none and craftily qualified by the very best in food, wine and entertainment. It was the biggest and best party of the whole voyage, and was on the tips of tongues for days proving a real morale booster for the trip south of the equator. The captain announced that the ship would sail close to the Cocos Islands and anchor there for a couple of hours in order to allow the locals to display their wares. Then it was full speed ahead for Freemantle where we went ashore on 24 July, 1958. There was nothing much and little action in Freemantle and so we joined a bus tour of the City of Perth. The highlight for most of us was a guided tour of the University with refreshments provided in a magnificent old building with spectacular views across the Swan River and parts of the city.

When we returned to the ship, everything was latched down for the trip across the Great Australian Bight. We spent most of this part of the journey indoors or in the sheltered parts of the decks. Many of the friendships formed during the voyage were about to come to an end as a number of passengers prepared to disembark in Adelaide. Among them was the McDavitt family and I knew that things wouldn’t be the same aboard without them. We had very little time together ashore before their transport arrived to take them to their first Australian home. Catherine and I corresponded for a number of months thereafter but didn’t manage to get together as promised for Christmas 1958. A few days after arriving in Adelaide, she was making her way to the Southern Flinders Ranges to a primary school about ten miles from the town of Laura. I often wondered what that must have felt like to an energetic, well-travelled, beautiful young lady brought up in Glasgow with a master’s degree from Edinburgh. In all probability, Catherine was the most academically qualified primary teacher in a South Australian school at that time.

Two days later, a small group of us including Tom Quigley from Dublin were having our first taste of real Aussie cuisine, steak and eggs, where Fr Paul Fitzgerald who had joined the ship in Freemantle had taken us for lunch to a club in Melbourne. I couldn’t get over how inexpensive it was compared to a similar meal in London. Before returning to the ship for the last leg of a really wonderful voyage, we spent the afternoon sightseeing in and around the city and riding the trams.

On the morning of 3rd August 1958, the ‘SS Orion”docked in Sydney. I disembarked to a very warm welcome that really exceeded my expectations. Mick, Bill McDonagh, Fr Con Sexton, Lenore Sowden and a host of others were there to greet me. It was absolutely lovely and took me completely by surprise. Fr Con who was Parish Priest of Dover Heights had two sisters who lived in my home town of Shrule. He had served as Chaplin to the Australian forces in Singapore and when it fell to the Japanese he was captured and imprisoned in the infamous Changi Prison until the end of the war. In fact Mick and his friends had organised a welcoming party the following weekend at the home in Lenthall Street Kensington where we were staying at the time. Everyone including the landlady enjoyed the evening and I met a lot of wonderful people.

A month or so later, Mick and I moved into a flat in Todman Avenue. I used to walk from there daily to the Motor Registry Department in Rosebery where I worked. Hardly a weekend went by without our calling to visit Fr Con and we weren’t the only

visitors. We had some great times at Dover Heights. It was there that I met Justice McKeown who persuaded me to take a teaching position at Waverley College at the beginning of 59. While there I enrolled in part-time studies at Sydney University and left Waverley at the end of 1960 to attend full-time. I completed my teacher training at Sydney Teachers’ College within the University and after taking up teaching at Punchbowl Boys’ High School I continued my studies at the University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

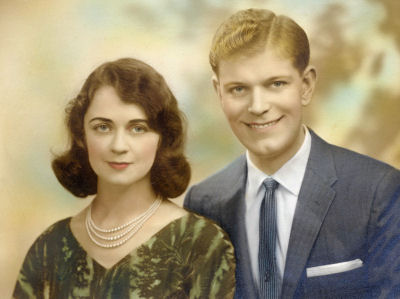

During Easter 1959, while on a trip to the Central Coast with some friends, I met Patricia Lynch, daughter of Tom and Margaret Lynch of Sydney. We were married on 2 January 1963 and so began another branch of the Coleman Clan. Photos of our five children appear at the beginning of this chapter. Tom Lynch's Grandfather and Grandmother, Michael Lynch and Mary Fitzgerald, were born in Patrick's Well, Co Limerick, and Limerick respectively. Margaret Lynch's parents were also from Ireland. Her mother, Bridget (Kennedy) Kearns, was born in Glown near Neanagh, and her father, Thomas Kearns, was born in Galway. Patricia has gathered over the years considerable information about her ancestry on both her father and mother’s sides of the family. I can recall the very special emotional impact the visit to Glown and the home of her Grandmother had on Patricia. It was wonderful to be part of it. Today, a very small part of that homestead in the form of a slate enjoys pride of place in our possession.

|

Patricia & Martin’s Engagement – April 1960

Back to Australian Branches ‹--------› Forward to Martin's Family Tree

Clan Coleman

Clan Coleman